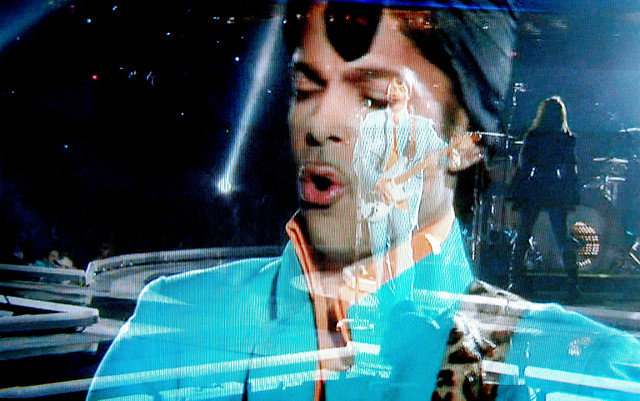

“Prince” by Ann Althouse/Flickr |

Cæli enarrant

The Lord God has opened my ear, and I was not rebellious, I did not turn backward.

—Isaiah 50:5

I’ve wrestled with pop music more or less since the first time I heard Toto’s “Rosanna” on the radio as a 9-year-old and found it stuck in my head. My center of music-listening gravity as a young adult settled on the 1970s: the decade built on a foundation of early and then maturing rock and roll, gospel, soul, and country, which gave flight to the ’80s, ’90s, and today. Many hits of the ’70s still swam in a broad spirituality of “love,” incorporating hoped-for social progress in a Christian or Christ-haunted key. One sees this in classic R&B (Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, Earth, Wind & Fire), rock and folk (Bruce Springsteen, Santana, Joni Mitchell), and of course country.

Socially minded love waned in American and British Top 40 — and politics — in the 1980s, and the solitary individual has dominated in decades since. Today, the lingua franca is money and sex, modified by dialects of disappointment, loneliness, lament, anxiety, and occasional resistance running round the edges, marking a main point of interest in contemporary pop (Arcade Fire, Sufjan Stevens, Ryan Adams, Radiohead). Lady Gaga’s body of work, like Beyoncé’s, fits here perfectly and to that extent is conformist, as are the anthemic cris de coeur that announce heroic resilience of a personal sort, like David Guetta’s “Bang My Head” featuring the amazing vocalist Sia (“now I know I will not fall / I will rise above it all”), or again, “Titanium” (“I’m criticized but all your bullets ricochet / You shoot me down, but I get up”).

The proliferation of popular I am hurt and wounded style-songs is sobering, the lyrics having moved well beyond the pathos of, say, Patsy Cline in their stark descriptions; nor, to be perfectly clear, are they operating within the semantic ambit of St. Paul’s cruciform expectation, fed by Easter joy: dying every day, “punishing my body and enslaving it, so that after proclaiming to others I myself should not be disqualified” (1 Cor. 9:27). The lyrical and cultural pattern also marks a devolution from the days of Fleetwood Mac’s “Second Hand News” (1977) or Joni Mitchell’s “Court and Spark” (1974), which still evince a fresh rebellion. In Joni’s careful placement of a come on amid social criticism: “All the guilty people, he said, they’ve all seen the stain / On their daily bread / On their Christian names / I cleared myself, I sacrificed my blues / And you could complete me, I’d complete you.” Who can argue with her transparent vulnerability in “Blue” or “Same Situation,” the more when set alongside the sassy genius of “Electricity” (“Well I’m learning / It’s peaceful / With a good dog and some trees / Out of touch with the breakdown / Of this century”)? The case of wine Joni could drink and still be on her heartbroken feet seems positively uplifting compared to Sia’s drunken stupor, swinging from a chandelier and “holding on for dear life” (one and a quarter billion views on YouTube). Similarly, the tender timidity of Joni frying up fresh salmon, seeking the undivided attention of her “sweet tumbleweed” of a man as a “Lesson in Survival” (1972), nakedness on the inside cover announcing bourgeois liberty, cuts a different figure entirely from the uncomfortable incoherence of the evocative dance jam “Take Me Home” (2013), featuring Bebe Rexha as a type of the wounded waif with a desperate need to be rescued into sexy unhealth (“My best mistake was you / You’re my sweet affliction / ’Cause you hurt me right / But you do it nice”).

It could be interesting to study when non-metaphorical wounds became mainstream in female pop ballads; perhaps Natalie Imbruglia’s smash hit “Torn” (1997) marks the shift: “I’m all out of faith / This is how I feel / I’m cold and I am shamed / Lying naked on the floor.” Fifteen years prior Prince delivered the studied shock value of “Sister” (not a single, tempered by the declaration of victory in “Uptown”), for which one is hard-pressed to think of a female analog at the time, save on the punk scene (e.g., Patti Smith). By the 2000s, dance music compilations routinely descended to a series of after-the-party lonely laments that would bum out Bryan Ferry, to say nothing of the Bee Gees; and here we find both the costume worn and the distance traveled by “the poor girl” to the chart-topping parties of today, in dark clubs with endless shots, on the other side of which erstwhile dancing queens can only hope to stumble home to parodied salvation. That is: “She’ll turn once more to Sunday’s clown and cry behind the door.” Madonna’s bubble-gum-plus-sex-and-synth beginnings and later, lightweight liberation (on a loop since the early ’90s) have given way to the typical pose of a Katy Perry as empowered woman on the far side of male control (“Roar” and “Dark Horse” both have ~1.3 billion YouTube views), but various stages of the painful battle occupy her most popular singles. In the video for “Part of Me” she becomes a Marine solely to shake her last cheating boyfriend; in “Wide Awake” she sits catatonic in a wheelchair before two menacing men wearing monstrous masks. And plenty of space is conveniently left for feminine commodification, not least as the occasion for Perry’s rise in the first place, which accounts for uncomfortable outliers from the main narrative like “E.T.” (“Take me, ta-ta-take me / Wanna be a victim / Ready for abduction”): whoops.

Dance as a popular genre across the decades — disco, techno, house, trance, dubstep, electropop, hip hop — consistently reflects the cultural debate about bodily discipline, tied to its DNA as a species of soul. Since the 1970s, the deep source of the scene has been American soul, replete with gospel-tinged lyrics: Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye follow Tina Turner and Otis Redding; Teena Marie and the Gap Band add synthesized funk; Prince and Madonna bring pop-rock and club elements that set the stage for a mainstreaming of all manner of drum & bass, electronica, ambient, and other experimental strands built on the soul foundation. British DJs like Groove Armada, Basement Jaxx, and Ben Watt of Everything but the Girl led the way in the late ’90s and early ’00s amid a spate of U.K. reissues of Parliament-Funkadelic, Curtis Mayfield, and other ’70s classics, and American pop and Top 40 followed, rediscovering their tradition with the help of R&B. Today’s most-celebrated Euro DJs have simply capitalized on the trend, placing soul-haunted dance at the top of the pop charts.

Were one to matriculate in this school, the elementary hooks of Ariana Grande (608 million views for the catchy Zedd-produced “Break Free,” replete with hyperbolic girl-power-cum-flirtation) would quickly give way to the vulnerability of Sia before alighting on more hope-filled alternatives, bearing seeds of the Church and her gospel, like the stand-out “Spectrum” featuring Matthew Koma (a mere 24 million views on YouTube) on Zedd’s Clarity, or again “Follow You Down.” In this way, students of pop music may learn to counter false religion (Acts 17:22), and every once in a while a Kim English comes along.

Is there a place in such a school for the retro-dance/electronic/hip-hop of LMFAO? Not in the way of daily bread, since the otherwise excellent “Party Rock Anthem” (1.1 billion views) peddles a muted debauchery that the rest of its catalogue clarifies and heightens; Philip Bailey and Michael Jackson would be disappointed. The seamier side of Rick James has become the norm, making non-sex-saturated soul an endangered species. If more synth-tastic dance is needed, prefer Zendaya’s “Replay” or Avicii or Passion Pit to most alternatives on grounds of light and life, including chastity. In the way of ambient funk, Groove Armada and Aphex Twin deliver depth and seriousness.

Of course, there’s much more. I haven’t discussed classic country or classic rock, ’80s rock, including emotive post-punk Brit pop, or the alternative scene of the ’90s and the burgeoning alt-country scene. In every case, ressourcement leads back to the O’Jays, the Spinners, Elvis, Sam Cooke, Martha Reeves & the Vandellas, and their sources in gospel and the blues. With roots identified and preserved, we can distinguish new growth and its edible fruit from destructive and poisonous weeds. Nothing more is needed in this field, save that the Lord himself open our ears (Isa. 50:5; cf. Rom. 10:17), so that our mouths may proclaim his praise.

Christopher Wells