Review by Daniel Muth

In the pages of the popular press, fever swamps both left and right, and those high priestly temples of modern America, courts and school boards, are ever-roiled by the fatuous and enervating “war of science and religion.” Front and center of this spectacle is that reliably malleable word, Darwinism, which at one moment refers to a particular and modest description of organistic development and at another to a purported Grand Explanation of All Reality. The uncertainties attending the term make it a useful foil for some fideisms and a potent cudgel to wield on behalf of others.

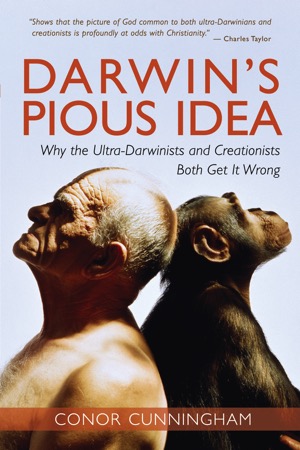

In his sprawling and iridescent tour de force, Darwin’s Pious Idea, Conor Cunningham of the University of Nottingham’s Center of Theology and Philosophy seeks to disarm at least two sets of extreme enemies of science: literalist Christians and materialist atheists. Since the latter have been more popular in academic circles, and successfully present themselves as defenders of science in the popular mind, Cunningham reserves the lion’s share of his book for their critique.

| Darwin’s Pious Idea Why the Ultra-Darwinists and Creationists Both Get it Wrong By Conor Cunningham. Eerdmans. Pp. 543. $35 |

He begins with a discussion of the “received view” of Darwinism, which claims that it revolutionized Western thinking. As part of his demonstration that this is not the case, Cunningham lays out the basic scientific tenets of the theory, and proceeds in succeeding chapters to bore through three inter-Darwinist debates. The first concerns the “units” of natural selection; that is, what is chosen among and what is selected for: genes, individuals, species, or something else? Cunningham describes the process as complex and the matter unsettled, though it is clear that the “selfish gene” concept is an oversimplification.

The second of the debates concerns whether natural selection is the principal evolutionary mechanism or just one of many, itself merely a statistical phenomenon. Cunningham argues for the latter, taking note of the obvious fact that natural selection acts as editor vice author, creating nothing. On this view, natural selection amounts to a diachronic phenomenon that may bring other possibilities into being but that is itself a creature, rather than engine, of evolution. Ultra-Darwinist overemphasis on the “universal acid” of natural selection makes it little more than a secular version of William Paley’s much derided watchmaker God.

The third debate concerns the extent to which directionality manifests itself in evolutionary biology. Positivistic assertions of progress are countered by more consequentialist rejections. There is movement both toward and away from variety and complexity: an ape may be said to be a higher being than an amoeba, but there were more body plans among Cambrian fauna half a billion years ago than now. Along the trajectories actually taken, greater complexity combines with vulnerability, with moral ambiguity attending the process at every point.

In every case, human intellectual capacity and subsequent transcendence of nature function non-artificially. Whether consciousness is a result of evolutionary intention or of a set of wildly unlikely coincidences is finally immaterial. On Cunningham’s account, humanity sits in its old position at the apex of creation.

In every case, human intellectual capacity and subsequent transcendence of nature function non-artificially. Whether consciousness is a result of evolutionary intention or of a set of wildly unlikely coincidences is finally immaterial. On Cunningham’s account, humanity sits in its old position at the apex of creation.

Cunningham next evaluates various attempts, via eugenics, sociobiology, and evolutionary psychology, to knock humanity off its high horse, as it were. The endeavor to apply evolutionary theory beyond the rarified climes of purely scientific investigation is as old as Darwin’s theory itself and has a solid track record of providing insight into human psychology and physiognomy. It has also been attended with pernicious nonsense.

Cunningham’s fair and often amusing acknowledgment of the former lends gravitas to his unsparing treatment of the latter. While eugenics may have died with Hitler, the impulse remains in reductionist forms of Darwinism. Cunningham quotes Philip Kitcher to the effect that one can hold bizarre theories about ant behavior or even the solar system without great tragedy ensuing. Matters are different with false understandings of humanity.

The next and longest chapter begins with an attempted dismissal of Intelligent Design unaccompanied by any investigation of either its scientific or theological implications. Having cursorily nodded in this direction, Cunningham returns to his objet de litige with ultra-Darwinism, critiquing both materialism and naturalism. He does this initially by busting the “science vs. religion” myth. In historical fact and by theological implication, science, including Darwinian science, finds no enemy in the Christian religion.

In fact, materialism fails at every level. Its inability to distinguish between living and dead organisms renders biology moot. Its old-timey atomism cannot withstand the reality of quantum physics and awaits the latter’s disproof. Its inability to explain, or even deal, with consciousness, the first of all human experiences, leaves it denying the existence of the scientist. Given its deification of science, it becomes the snake that swallowed itself.

Finally, Darwin’s Pious Idea ascends to a robustly theological rejoinder. Church Fathers in hand, Cunningham eschews readings of early Genesis or of the Fall as an event rather than a condition. Because God is natural and the created order supernatural, human beings are made in the image of God in and through Christ, for and through whom all else is created.

Adam’s sin was to take life as a given rather than a gift, to seek to be self-created and therefore dead. In Christ’s life we see the abnormality — the unnaturalness — of death. Death is not reconciled with life, but overcome by bodily resurrection.

In many ways unwieldy and repetitive, Cunningham’s argument often amounts to a stream of consciousness. Yet, as in David Bentley Hart’s writings, this serves a larger purpose.

The science of evolutionary biology has found what it has found — and what it has found matters. Creation matters so much that God himself entered and died within it. In obedience to God, Christian theology places scientific knowledge in the context of revealed truth. Darwin’s Pious Idea follows this tradition in striking fashion.

Daniel Muth, principal nuclear engineer for Constellation Energy, is secretary of the Living Church Foundation’s board of directors.

Image of Charles Darwin via Wikipedia Commons

TLC on Facebook ¶ TLC on Twitter ¶ TLC’s feed ¶ TLC’s weblog, Covenant ¶ Subscribe