By Tom Sramek, Jr.

From The Living Church

June 6 edition

Perhaps it is human hubris for a generation to see itself living in a pivotal time. But with the rise of unaffiliated “nones,” disaffiliated “dones,” and a church that can no longer count on inertia or brand loyalty, the 78th General Convention at least meets in turbulent times. When the 75th General Convention met in Columbus, Ohio, in 2006, seven nominees stood for election. Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori has served through a tumultuous and in many ways transitional period in the history of the Episcopal Church.

Beginning June 25, bishops and deputies will tackle proposed legislation on same-sex marriage, liturgy, and various topics of justice. But a clear central theme will be the health of the church and whether it is prepared for effective ministry in the still-young 21st century. The election will occur amid discussions of the Task force for Reimagining the Episcopal Church’s report and the subsequent “Memorial to the Church” endorsed by many bishops and deputies. That restructuring may include changes in how the presiding bishop engages with the broader church.

Digital culture already has affected the presiding bishop’s work. When Bishop Jefferts Schori was elected the iPhone had not yet been introduced, Facebook had just been made available to users other than university students, and YouTube and Twitter were still finding their core audiences. The church now functions in an immediately global context, in which a tweet, a text message, a podcast, or a video sermon may quickly find a global audience. At the same time, hands-on ministry occurs mostly in dioceses and congregations.

Into this tide of change and challenge walk four nominees who have agreed to stand for election as the 27th presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church. There are no women this time. All four nominees are in their late 50s or early 60s. Their tenure as diocesan bishops ranges from five years (Ian Douglas), to eight (Thomas Breidenthal and Dabney Smith) to 15 (Michael Curry). The Living Church offers a glimpse into each nominee’s vision for ministry and the Episcopal Church’s future, based on interviews with each man.

Thomas Breidenthal

Thomas Breidenthal

Ancient witness, open mind: the church at its best.

Thomas Breidenthal held a variety of positions in the church — parish rector, school chaplain, seminary professor, and university dean — before being elected Bishop of Southern Ohio. As a parish priest in Oregon, he observed that not only is the church increasingly on the margins but faith itself is an anomaly in many parts of the country. This demonstrated to him the increasing need for ecumenical and interfaith partnerships. He appreciates, for instance, the increasing fascination of evangelical Protestants with sacramental worship and work for justice.

He expresses concerns much like those of the Task Force for Reimagining the Episcopal Church (TREC). “We are to approach every neighbor as one for whom Christ died, and we are to trust that the God who made us for community can take whatever is most broken in our relationships and heal it,” he said. “So we must always face where we are with one another and work from there, without pretense, but with real commitment to the kingdom of God, of which we are the raw material.”

Such engagement with neighborhoods would be a central theme in his tenure as presiding bishop: “Were I to be elected presiding bishop, I would use that office’s pulpit to drive home the local congregation’s crucial role in living out connection every which way.”

What the Episcopal Church has to offer the world, and especially the unaffiliated, is a “firm grounding in the mainstream of Christian teaching coupled with a hard-won and well-honed ability to tolerate disagreement among ourselves.”

What we often lack is an ability to talk about our faith. In this, evangelicals have something to teach us. “Evangelicals are becoming attracted to liturgy, and are feeling uncertain in the face of that,” he said. “Likewise, we who are quite comfortable with liturgy are inching toward witness. The same Spirit is pushing both traditions to a new meeting place. What will it look like when evangelical liturgy and liturgical witness come together?”

How does he see the role of presiding bishop? Breidenthal sees it as largely a teaching role. He sees a presiding bishop as someone who empowers others to use their gifts and talents. The Episcopal Church works best when widely scattered individuals, congregations, and dioceses see themselves as a part of a larger whole.

Breidenthal sees some difficulties in TREC’s proposal that the presiding bishop be CEO of the church. “The presiding bishop,” he said, “is not a CEO hired by a board, but a pastor elected by fellow bishops to focus their spiritual leadership of our branch of Christ’s church.” Accordingly, the presiding bishop is accountable to “the community of bishops, and on that basis, stands in collegial relationship with Executive Council.”

He believes that acknowledging differing convictions and respecting them is an important way to unite the various factions of the Episcopal Church. “In a fairly moderate to conservative diocese, I have brought people to agree to the blessing of same-gender unions, and have publicly promoted health-care reform and care for immigrants in the name of the diocese,” he said. “How was this possible? I think people trust me to listen to all sides, and to act out of my own Christian (rather than merely partisan) convictions, as well as a considered sense of what we as a diocese can live with. Respect and acknowledgment go a long way.”

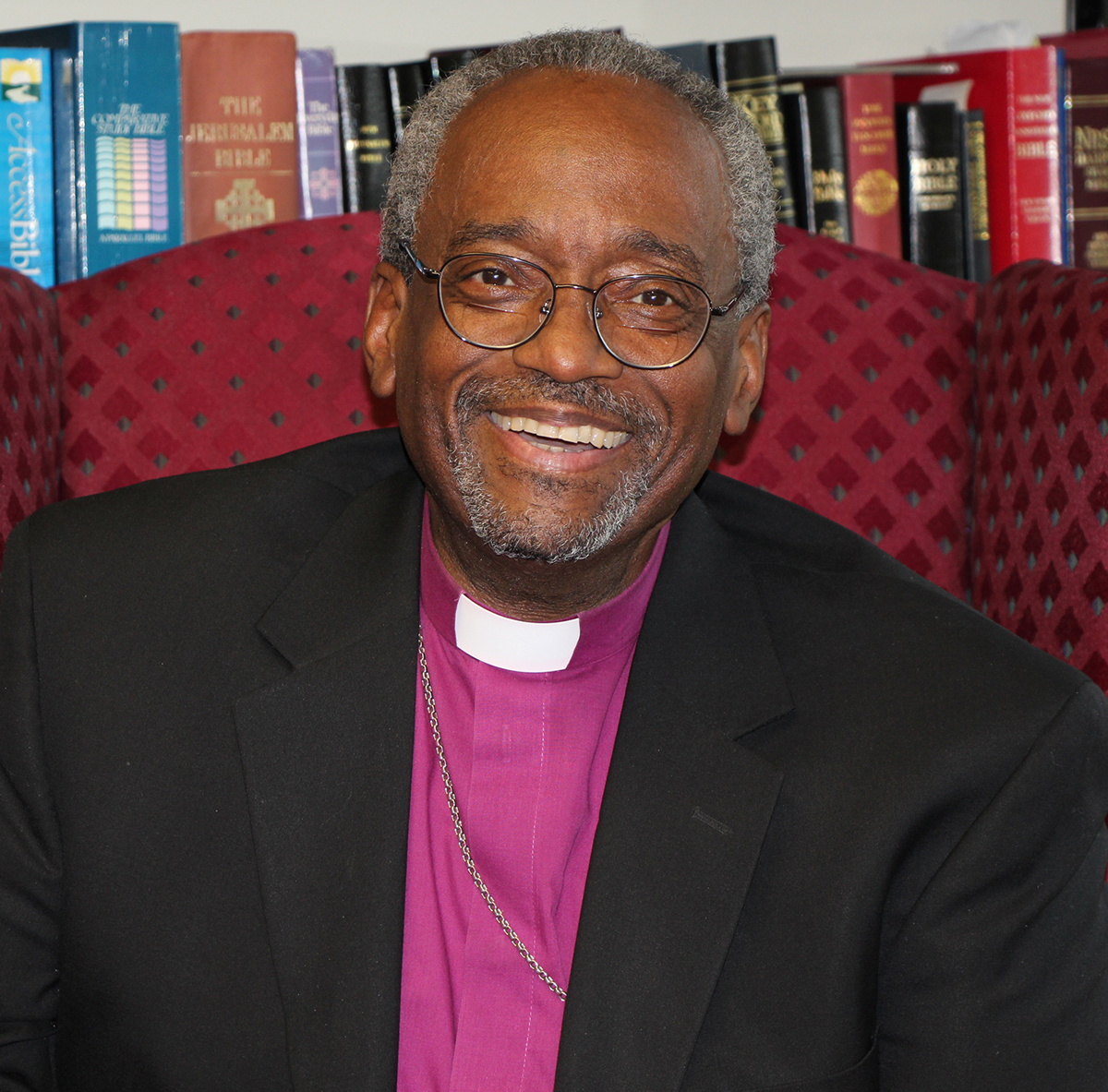

Michael Curry

Michael Curry

Tweet the vision, then help people make it happen.

Michael Curry stands as one unapologetically focused on making disciples of Jesus. “I think that the primary business of the church is to form and make disciples of Jesus — and that makes a difference in the world.” As Bishop of North Carolina for 15 years, Curry feels open to a new chapter in that work or to beginning an entirely new chapter as presiding bishop.

“While a presiding bishop has important responsibilities as CEO (Chief Executive Officer), I believe this mission moment in which we find ourselves demands a presiding bishop be a CEO in another sense: Chief Evangelism Officer,” he said. “That approach seeks to live out the meaning of the Great Commission to ‘make disciples of all nations’ and is how we share in the Jesus movement of our time, making a difference in our world through evangelism, personal and social witness, and prophecy.”

Curry believes that social media offer opportunities to be “a messenger of God’s loving, liberating, and life-giving word in Jesus the Christ” to a global audience. “Today [the presiding bishop’s] pulpit is not just of wood or stone,” he said. “It is digital. Sometimes it is a tweet, sometimes a post on Facebook or Instagram, sometimes an article online and in print, and very often personally preaching and teaching.”

In involves “listening and encouraging the faithful people of God in their discipleship, following in the way of Jesus.” He has experience with digital media, having “all of these means, in addition to a weekly video message or interview,” to communicate with his diocese. In a coordinated and strategic way, a presiding bishop can utilize these and other vehicles as means of evangelism, encouragement, formation, teaching, and proclamation.”

Far from believing that Christianity is dying, Curry thinks the church’s best days are still ahead. What is coming to an end, he said, is nominal Christianity, Christianity as simply membership in an organization. The death of that type of Christianity leaves an opportunity for real Christianity: loving God and loving our neighbor as Jesus did.

He remembers a remark he heard long ago: someone who is really studying and following the path Jesus took, and doing the things that Jesus did, cannot help but change the world. It is with that sort of Christianity that we can “live and survive as people of the Spirit.”

What about the many restructuring discussions scheduled for General Convention? Curry said the church’s task is not organizational development but community organizing — getting out into the world and engaging the world with the gospel so that people “run into Jesus when they run into us.” He suggested that the Episcopal Church could focus on four dimensions of sharing the good news: formation as disciples of Jesus, encouraging and fostering networks and ways of training and support, supporting evangelism initiatives through churchwide resources, and, supporting all of these, “the direct evangelical ministry of the presiding bishop.”

Within the church, mission requires moving beyond an immediate crisis to a vision of something more. In his diocesan work, “having an overarching and compelling vision that summoned us beyond the immediate toward the ultimate really made a difference,” Curry said. “Having that greater mission vision gave us a reason for being and gave us direction. And that sense of direction guided our discernment and helped us make a decision consistent with the mission vision. The vision ultimately set us free to decide. The King James Version of the old saying in Proverbs was true — ‘Without a vision the people perish’ (Prov. 29:18). And the corollary is even more true: With a vision there is always a new possibility.”

Ian Douglas

Ian Douglas

Think globally, act locally — together.

Ian Douglas sees his participation in this election as part of a continual and lifelong process of discernment. He has studied Christian mission formally but has not served as a rector. He likely has the most experience with the structures and processes of the Episcopal Church, having served as a Volunteer for Mission in Haiti and then as the Episcopal Church Center’s associate for overseas leadership development in the 1980s.

He served as a consultant to the Most Rev. Frank T. Griswold, the 25th presiding bishop, during the last half of Griswold’s tenure and in dozens of other positions within the wider church and the Anglican Communion. Douglas said he is able to hold such structures and processes lightly and recognize both their utility and their transience in an increasingly connected and networked world.

“In the 20th century, organizational models of the corporation (National Council) and the regulatory agency (Executive Council) made sense,” he said. “In the postmodern, post-Christendom, digitally networked world in which we now live, 20th century organizational structures have lost most of their efficacy.”

“Local congregations are appropriately concerned with local needs,” he said. “Extra-diocesan” structures are ebbing away and, in fact, have been fading since the 1970s, when the Episcopal Church Center employed more than 400 people. As someone who experienced the reduction of that staff during his tenure there, and now as a diocesan bishop, he understands both the strengths and the limitations of a central structure.

In the Diocese of Connecticut, he was a driving force behind selling the “diocesan mansion” that served as headquarters and moving into an open, shared, and rented space in a converted ball-bearing factory. “The Commons,” he said, “is an icon of our new commitment to transparency, flexibility, and collaboration across the parishes in the Episcopal Church in Connecticut.” As presiding bishop, Douglas said, he would “assist bishops to imagine new ways, and try experiments, in their own contexts and dioceses that would foster collaboration and new commitment to God’s mission at the local parish level.”

As a student and teacher of missiology, Douglas is wary of what the late Rabbi Edwin Friedman would call “technical fixes” as a cure for what ails the institutional church. “The question before us as the Episcopal Church is not so much a need to clarify roles,” Douglas said, “but rather the much larger question of how we understand the mission of God in the world today and how we as Episcopalians can best serve that mission in our local parishes, in our dioceses, and at the pan-diocesan level.”

As a member of the Anglican Consultative Council and the more recently designated Anglican Communion Standing Committee, Douglas has seen the Communion change from a largely Anglo-centric institution to one in which bishops and others of the developing world have found and claimed their own voices. The realities of globalization and digital communication are simultaneously pulling us together as a church and driving us apart.

“We exist because we are a part of the body of Christ,” Douglas said. “If we are going to be faithful, we need the other who is radically different from who we are.”

Douglas said he is committed to the sort of evangelism that crosses boundaries and restores wholeness. “I believe that in Jesus, fully human and fully divine, God crossed the boundaries, division, and alienation that separate us from God, from each other, and from all creation,” he said. “In Jesus, God has restored all people to unity with God and each other in Christ. As presiding bishop, I would invite all Episcopalians to own their baptismal call to be evangelists of the good news of God in Christ as they participate in God’s mission in the world.”

Dabney Smith

There are no “discards.” Love one another.

Dabney Smith initially resisted the call to stand for election as presiding bishop. He is bishop of a healthy diocese located in the state from which he hails and in the area of the country where he has spent the bulk of his ordained ministry. Eight years into his episcopate, he is reaping the rewards of the hard work done by him and those whom he leads. “It’s not about you, it’s about the church,” one of Smith’s fellow bishops said when he was nominated. As a result, he sees standing for nomination as an offering to the church.

As Episcopalians engage the modern world, Smith believes that evangelism provides both capacity and motivation to tell our story. “The religious landscape of the world is ever evolving,” he said. “The love of God through Christ for us remains consistent. Episcopalians have the capacity to be effective evangelists. Like any other Christians, we simply have to know our own stories honestly, to reveal joyfully how we’ve been called, changed, and claimed by Christ.”

How does he see himself changing the role of presiding bishop? “My proposals before General Convention are simple: name, identify, and clarify the perceived problems in our polity; allow time within our existing polity to practice ideas, such as the unicameral house,” Smith said. “This would give us patience and wisdom to gain perspective for purposes of both positive impact evaluation and the weighing of consequences of our potential decisions before making them canonical.”

Bishop Smith is clear on the need to ground leadership in prayer. “I have discovered that being bishop is a humbling experience, in that my personal prayer life has been so challenged and enriched by the call,” he said. “The demands, personalities, administrative issues, discernments, conflicts, and mission opportunities reveal a deep well of need for divine wisdom. The structure of the Daily Office is foundational for me in keeping rooted in the prayers of the church while I pray of the needs for the church.”

He is similarly passionate about the health of congregations: “As presiding bishop I would hope to maintain my outlook on the need to continue the work on the building up of strong, local congregations. The Episcopal Church itself is as strong as our local faith communities. I would work with seminaries, theologians, diocesan schools, fundraisers, the General Convention, the Executive Council, the bishops and leaders in the House of Deputies to maintain this focus. I would teach and encourage congregational health and vitality in every diocesan visitation. The big picture of our whole church and the global Anglican Communion is intimately connected with each congregation.”

Does Smith perceive himself as “the conservative candidate”? He said he has been characterized in a variety of ways throughout his ordained ministry, likely depending on who describes him. He gives the impression of striving to do a great deal of listening, and he wants to honor and trust churchwide discernment in all areas: structure, liturgy, the canons. He is unlikely to enforce conformity or advance his own agenda, but would instead reflect the agreed-upon agenda and priorities of the wider church as expressed through General Convention.

How would Smith keep people of widely differing opinions in relationship with one another? Our “baptismal wisdom” teaches that there are no “discards” (disposable people) in the church, he said, but that we are all in this together and called to be diligent about fostering connection, even as we disagree about a range of issues. To love one another is “divine, demanding work that changes one’s soul.”

“Every opinion one can find in the Episcopal Church will be discovered in the Diocese of Southwest Florida,” he said. “The opinions will be voiced, though, in a collegial, supportive atmosphere. Unity does not require agreement, but an awareness of the God we serve.” He would “seek to bring people together for the same result” as presiding bishop. “We do not need to agree,” Smith said. “We do, though, serve the same Lord.”

The Rev. Tom Sramek, Jr., is co-rector of Good Samaritan Church, San Jose, California, and writes at bloggingpriest.blogspot.com.

TLC on Facebook ¶ TLC on Twitter ¶ TLC’s feed ¶ TLC’s weblog, Covenant ¶ Subscribe